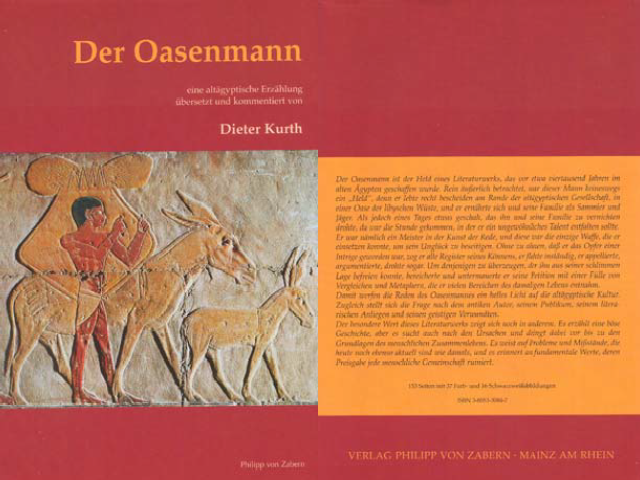

Kurth, D. 2003. Der Oasenmann. – Mainz am Rhein, Verlag Philipp von Zabern (Kulturgeschichte der antiken Welt 103)

Abstract

The composition known to English–speaking Egyptologists as ‘The Eloquent Peasant’ has long been seen as a central work of ancient Egyptian culture. As with much ancient Egyptian literature its modern reception has been varied, from Gardiner’s (1923: 6–7) dismissal of the author as “anything but a literary artist” to Parkinson’s (1997: 54) reading of the tale as a complex, ambiguous and highly literary work of “studied simplicity”. Kurth’s book is an admirable attempt to present the tale to a modern audience as a contextualised work of ancient literature. A monograph on what is, by modern standards, a rather short story, is an opportunity to present it in more depth than what is possible in more general volumes of translation of ancient Egyptian literature. Kurth, who has divided the book into two distinct parts representing two different approaches to the text, exploits this opportunity to great effect. The first part, which accounts for just under half of the book, deals with context. In the chapter entitled ‘Die Geschichte des Oasenmannes als historische Quelle’ (pp. 14–42), the author looks at various aspects of the socio–geographical environment in which the story is set, like the possible route taken by the protagonist from his home Salt–marshes (sxt-HmAt) in the Wâdi el–Natrûn into the Nile Valley. Other subchapters on the philosophical principles underlying the peasant’s petitions, on the justice system evident in the petitioning process and on the technicalities of sailing on the Nile are informative and serve to anchor the text in its socio–historical context. A second chapter looks at the story as a work of literature (‘Die Geschichte des Oasenmannes als Literaturwerk’, pp. 42–58), the intent of the ‘author’, and the ways in which the work may have affected those who read or heard the story in antiquity. He points out the possible function of the text as a ‘Beamtenspiegel’ for the bureaucracy, and draws parallels to the mediaeval speculum regum genre, but this reading may over–emphasise the text’s didactic aspect: in the absence of any evidence of reader reception (much less any ancient works of literary criticism), a less functionalistic approach is perhaps preferable. The last section before the translation itself, entitled ‘Wie fern ist die Antike?’ (pp. 58–65), points out some of the problems modern readers face when approaching a 4000–year old literary work, and highlights the two conflicting aims which influence the modern study of all ancient literature. These are on the one hand the desire to transmit it as literature, to let the reader experience the story free from philological crutches and footnotes, and on the other hand the desire to present it as a historical artefact embedded in its cultural context. Both are laudable aims in and of themselves, but they are not easily combined. Read more...

Downloads